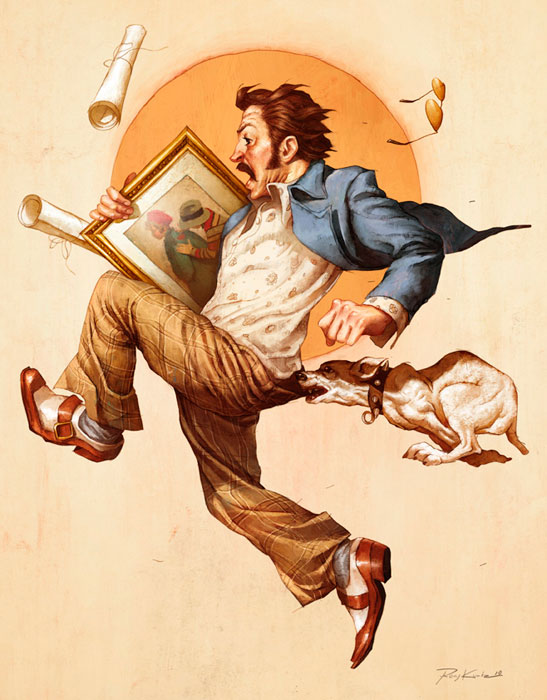

Rory Kurtz | The Heist For Minnesota Monthly

October 27, 2010

Levy Creative Management artist RORY KURTZ illustrates a great piece to an amazing story about Norman Rockwell for Minnesota Monthly.

The Heist

One wintry night in 1978, a band of thieves stole seven Norman Rockwell paintings worth more than $500,000 from a St. Louis Park art gallery. Two decades later, after most leads had gone cold and the FBI had closed the case, the paintings surfaced. Here, the untold story of where they went and how they were found.

On February 16, 1978, more than 500 people gathered at Elayne Galleries in St. Louis Park to drink champagne, eat cake, and celebrate Norman Rockwell’s 84th birthday. The famed painter of iconic American images wasn’t present, but several of his works were on display. The gallery’s owners, Elayne and Russ Lindberg, had a national reputation for handling Rockwell’s works and had organized the largest exhibition of his work ever assembled in a private show.

The show had all the trappings of a major opening. It featured roughly three dozen pieces, including eight original Rockwell paintings, numerous Rockwell lithographs, and a seascape attributed to French impressionist Pierre-Auguste Renoir. Four of the Rockwells, titled So Much Concern, The Spirit of ’76, Hasty Retreat, and Lickin’ Good Bath, were on loan from Brown & Bigelow, the St. Paul calendar company that had been commissioning images from Rockwell for reproduction since the 1920s. Two additional Rockwells—Boy Scout and She’s My Baby—had been borrowed from private owners.

The Lindbergs rounded out the show with a pair of paintings owned by the gallery itself. These two pieces, collectively titled Before the Date, were especially valuable, because they were among the last pictures Rockwell had created for the Saturday Evening Post. They depict a teenage girl and her boyfriend, each getting dressed to go out on a date. The girl is bending toward the mirror in front of her, and the way her slip clings to her was too risqué for the Post. When the magazine’s editors altered the image and published it without Rockwell’s consent, the artist was upset. That incident hastened the end of his decades-long relationship with the publication.

In total, the works were valued at more than $500,000. Given the paintings’ prestige and provenance, security was a serious concern. The year before the Rockwell show, the Lindbergs, who had been in business for nearly a decade, had relocated to a 2,000-square-foot-space on Excelsior Boulevard and had hired a contractor to make the gallery theft-proof. An alarm system was installed, and a Pinkerton guard was retained for the duration of the Rockwell exhibit.

But sometime after the birthday party ended, after the guests had gone and the Lindbergs had driven home, a band of thieves punched the lock on the gallery’s back door and disabled the alarm system. Seven of the eight Rockwells and the Renoir were stolen. Oddly, the Pinkerton guard was missing in action while the theft took place. (“No one has ever figured out where he was,” says Bonnie Lindberg, Elayne and Russ’s daughter, who joined the business in 1976.) But it was the guard who discovered the theft.

It was—and remains—the biggest, priciest, and most infamous art theft in Twin Cities history.